wasat

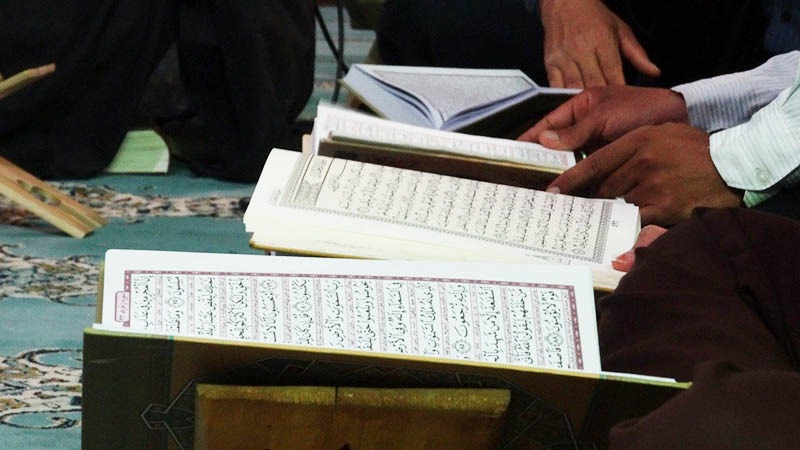

The Muslim Ummah – A Moderate or A Justly-Balanced Community

01 October 2020 12:03 am // Written by Muhammad Mubarak Bin Habib Mohamed, Dr.

This short article argues that the word moderate, as the English translation of wasaṭiyyah, is an inaccurate translation to denote the identity of the Muslim ummah. A more accurate translation that described the identity of the Muslim ummah and encompassing more dimensions is a justly-balanced community.[1]

This argument is based upon two factors. Firstly, the English meanings of the word moderate do not accurately render most of the dimensions and meanings of wasaṭ as used in the Qur’an to describe the Divinely-ordained identity of the Muslim ummah. Secondly, the word moderate is a convoluted word that pre-supposes many assumptions and inherent political positions. It has been and still is used within a political context where it takes various meanings in different parts of the world. Its usage is directed towards mostly Muslims by political powers who intend to identify groups of Muslims whom they see to benefit the political ideologies and agendas of the governing powers. We will describe the above points in the subsequent parts of this article.

Moderate, moderates and moderation

The word moderate, is a noun, with a plural of moderates. As an adjective, moderate means “staying within limits that are considered to be reasonable by most people”[2] or “done or kept within sensible limits.”[3] Moderate as an adjective for ideas is also confined towards politics as those that “…are not extreme and are therefore acceptable to a large number of people.”[4] In its verb form, moderate means “…to become or make something become less extreme, severe, etc”[5] or “…to (cause to) become less in size, strength, or force; to reduce something.”[6] Moderation means “…the ability to keep one’s feelings, desires and habits within reasonable limits”[7] or “…the quality of being reasonable and not being extreme.”[8] The word moderation is seen to be used interchangeably with words like “average”, “core”, “standard”, “heart” and “non-aligned.”[9]

In the Western media and political discourses, moderates and moderation often denote a label or a calling to the Muslims. Seldom, this calling is addressed to the other religious groups, like the Buddhists in Myanmar, the Ku Klux Klan white supremacist movement in the United States or even the Army of God which is a Christian extremist movement.

This term is also not used to address countries like the United States and the Israel whose military policies and behaviours are far from being moderate. The Israelis will punish severely the slightest provocations from Palestinian children with military actions under the excuse of defending themselves against extremist Palestinian children. The United States will support the actions of the Israeli military forces without the slightest sympathy and empathy of the plight of the Palestinian people.

US hegemonistic purposes of exhibiting its supremacy and as the world superpower and police can be seen from its hundreds of military bases around the globe, which is far from the idea of being moderate and practicing moderation in trusting the respective political leaders. Moderation makes no sense in these distorted instances where justice is ignored.

In another example, the war on terror in the aftermath of September 2001, the arrest of Jemaah Islamiah and with the current ISIS threat pulled the periphery jihadist towards the centre of Islam. The longer the military campaigns carried out by Washington, the louder will be the voices of these peripheries. Moderate Muslims are demanded to respond and take a stand against isolated, unrelated acts of terror done by these people who profess the belief of Islam. Muslim groups, individuals and organisations that do not speak out against these groups are targeted and labelled to be supportive of the jihadist and are not moderate Muslims.

In another contextualised usage of moderates and moderation is also seen in the labels given to Muslims in Muslim-majority countries like Indonesia. These terms are used to describe the ‘liberal Muslims’ and the ‘secularist Muslims’ who advocate fundamental changes to the interpretations of the Islamic Intellectual Tradition with questionable Islamic authenticity. They advocate progressive Islam by embracing modernity and are described to be moderates by certain factions of political powers and the media. Their disguise of progressive Islam, makes the majority of Muslims in these countries be deemed as extremists or fundamentalists. In both these cases, the usage of the terms moderate and moderation distort the intended meaning of wasaṭ as a Divinely-ordained identity which marginalise the silent majority of the Muslims.

Moderation is also sometimes equated with mediocrity and neutrality which lack enthusiasm and the willpower to put in the best. This results in an image of Muslims, either individually or collectively as a community which lacks excellence and dedication in pursuing and aiming for the best. This word when used within the context of a traditional Muslim family or culture denotes a compromise on religious principles or religious duties in order to appease others who view Islam as a set of dogmas and doctrines that are archaic in contemporary times. The different usage of the words moderates and moderation are “often contextualised…given different readings in different parts of the world” strengthen our argument that using this word to describe the identity of a collective Muslim ummah who is made up of many different languages, ethnicities, cultures and even political environments distort the different shades of intended meanings of the word wasaṭ as used in the Qur’ān.

Wasaṭ as a divinely-ordained identity of the Muslim ummah

The linguistic use of wasaṭ in the Arabic language denotes the meanings of “…superiority, justice, purity, nobility and elevated status.”[10] The Qur’anic usage of this term in describing the ummah (2:143) denotes a divinely-ordained identity of the ummah as being the best ummah God has created (3:110) which is dedicated in “…promoting good and preventing evil, its commitment to building the earth and implementation of justice therein.”[11]

Linguistically, the English word moderate, applied on its own, is not able to capture the meanings of wasaṭ and when it is used to describe the identity of a community, the words moderate and moderation lose most of the dimensions of this Qur’anic description.

The word moderate fails to give the idea of a community of excellence, an exemplar community, a community that is committed towards truth and justice, a community that balances between two extremities in areas of economic doctrines, political ideologies and material developments.

Many contemporary Muslim scholars have attempted to translate this Qur’anic identity of the ummah with various translations. Some of these are “ummah of the golden-mean”[12], “a middle community”[13], “an Ummah justly balanced”[14], “a community of the middle way”[15] and many others. We would like to argue that the phrase ‘justly-balanced’, as a translation for wasaṭ, reflects more accurately the intended identity of the ummah as used in the Qur’an. This is based upon the linguistic meaning of the word justly-balanced and the historical trajectories of the ummah as the backbone of the Islamic civilisation.

Before we proceed, let us examine the elaboration of Abdullah Yusuf Ali in describing the ummah as a justly-balanced ummah. He said,

“The essence of Islam is to avoid all extravagances on either side. It is a sober, practical religion. But the Arabic word wasat also implies a touch of the literal meaning of intermediary. Geographically, Arabia is in an intermediate position in the Old World as was proved in history by the rapid expansion of Islam, north, south, west and east.”[16]

His argument of the selection of the phrase “justly-balanced” as the most appropriate translation is based upon the essence of Islam that shuns extremes. In addition to his description, the phrase “justly-balanced” adds an adverb to the adjective balanced. The adverb “justly” gives an answer to the question of “in what manner has the balance been done?” The answer would be the ummah gives equal attention to all sides and considers various opinions and options in a morally right and proper way. An adverb also adds a degree of intensity to the adjective that is used. The nature of the ummah is always then defined by a balanced thinking, acting and believing.

The Muslim ummah is described as a justly-balanced ummah not just due to its geographical position, but as the backbone, creator, torchbearer and sustainer of the Islamic civilisation. Without the ummah, there is no Islamic civilisation.

Our Intellectual Tradition shows that the ummah, as a collective whole, has largely succeeded in charting the “middle path” in the pursuit of spiritual life, intellectual development or material pursuits.

The Muslim ummah has generally shunned the excessive pursuit of material wealth and physical development at the expense of spiritual, intellectual and moral development.

The traditional Muslim ummah has always enjoined and supported the twin partners of the ‘ulama’ (religious leaders) and umara’ (political leaders) to lead the ummah in traversing the religious and political terrains of time.

Without doubt, there were and will be occasions that the ummah fail to live up to the ideals and expectations of the Qur’anic injunction of being a wasaṭ community However, it does not disqualify them to be described as a justly-balanced community. The Qur’ānic description of the Muslim ummah shows an inter-civilisational context where they are acknowledged by other communities as those who are committed towards mercy, justice, compassion, uprightness and truth. The Muslim ummah has a connection with the past and present nation, its civilisational roles and commitment to stand for an order of values. The usage of wasaṭ in this verse is transitive which means that “it is not self-contained in itself unless it is applied to a subject that it can qualify.”[17]

To be a witness of other communities does not signify “superiority of this ummah over other nations who were recipients of divine guidance and prophets that delivered God’s messages to them and advised them”[18] but a commitment towards excellence in the holistic development as a collective entity or as an individual. The testimony in the verse indicates the honour Divinely bestowed on the Muslim ummah and simultaneously a Divinely ordained responsibility the ummah has towards the human civilisation.

Conclusion

No singular English translation will be able to capture the whole range of meanings that the word wasaṭ, as a Qur’anic identity for the Muslim ummah, has. Nevertheless, we must not conveniently select an English word to translate any Qur’anic concept without paying attention to the nuances of the languages. The search for the best translations of Qur’anic concepts continues as Arabic is a Divinely selected language of communication between the Divine and creations.

Footnotes

[1] Dr Muhammad Mubarak received his PhD in Islamic Civilisation and Contemporary Issues from the Sultan Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Centre for Islamic Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam. He obtained his Master of Arts in Islamic Spiritual Culture and Contemporary Society from the International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilisation (ISTAC), International Islamic University of Singapore. He also holds a Master degree in Education in Curriculum and Teaching from National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University. He is currently the Chairman for Centre for Contemporary Islamic Studies (CCIS), Singapore.

[2] https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/moderate_1?q=moderate, accessed on 22 March 2020.

[3] Longman Dictionary for Contemporary English (New Edition), (England: Longman Group UK Limited, 1987), p. 668.

[4] https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/moderate, accessed on 22 March 2020.

[5] https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/moderate_2, accessed on 21 March 2020.

[6] https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/moderate, accessed on 21 March 2020.

[7] Longman Dictionary for Contemporary English (New Edition), (England: Longman Group UK Limited, 1987), p. 668.

[8] https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/moderation?q=moderation, accessed on 22 March 2020.

[9] Mohammad Hashim Kamali, The Middle Path of Moderation in Islam: The Qur’anic Principle of Wasaṭiyyah, (University of Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 9.

[10] Abu Ibrahim ‘Abd Al-Wahid bin Yusuf Al-Sharbini (2010), Al-Qaṣd Wa Al-Wasaṭiyyah Fi Daw’ Al-Sunnah Al-Nabawiyyah, Riyadh: Maktabat Al-Rushd, p. 59.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Isma‘īi Raj`i Al-Faruqi (1992), Al-Tawḥid: Its Implications for Thought and Life (2nd ed.), Hendon Virginia: International Institute of Islamic Thought, p. 122.

[13] Seyyed Hossein Nasr (chief editor) (2015), The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary, New York: HarperOne, Kindle edition 13 of 1988.

[14] Abdullah Yusuf Ali, The Holy Quran, (n.p, 1946), p. 57. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/HolyQurAnYusufAliTranslation1946Edition/page/n55/mode/2up accessed on 22 March 2020.

[15] Muhd Asad, The Meaning of the Quran, p. 61. Retrieved from http://www.muhammad-asad.com/Message-of-Quran.pdf, accessed on 22 March 2020.

[16] Abdullah Yusuf Ali, The Holy Quran, (n.p. 1946), p. 57. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/HolyQurAnYusufAliTranslation1946Edition/page/n55/mode/2up accessed on 22 March 2020.

[17] Mohammad Hashim Kamali (2015), The Middle Path of Moderation in Islam: The Qur’ānic Principle of Wasaṭiyyah, University of Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 11.

[18] Maḥmud b. ‘Abd Allah Al-Alusi (n.d.), Ruh Al-Ma‘ani Fi Tafsir Al-Qur’an Al-`Aẓim, (Vol. 3). Beirut: Idarat Al-Ṭiba‘ah Al-Muniriyyah, p. 11.